About shakuhachi notations

Opening your repertoire

Frédéric Boulanger

frederic.boulanger.fbo@gmail.com

World Shakuhachi Mentoring Day – March 30 2025

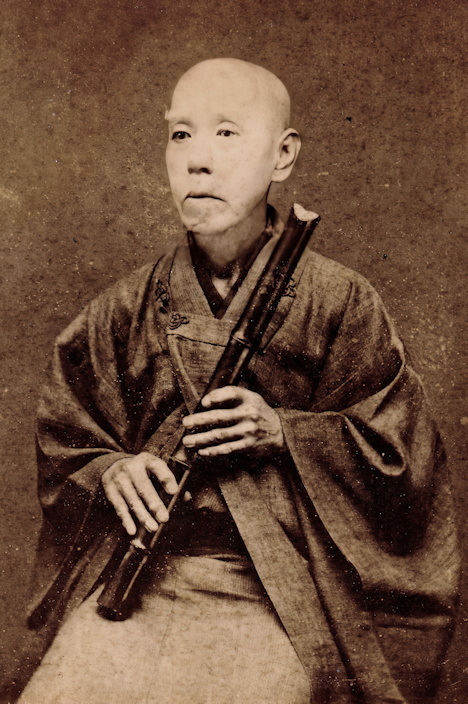

About me

Frédéric Boulanger

Professor in Computer Science at Université Paris-Saclay

I play the clarinet and bass clarinet as a hobby

I have developed an interest in the shakuhachi since 2010:

- Began with a DVD by Gunnar Jinmei Linder (first piece was Hi Fu Mi 😅)

- Participated in masterclasses, summer schools, workshops, ...

Now:

- I study the Tozan and KSK styles with Jean-François Lagrost (Shin Tozan ryū)

- I study the Kinko Chikumeisha style with Gunnar Jinmei Linder (Chikumeisha)

- I study Japanese traditional and contemporary ensemble music

with Mieko Miyazaki and Jean-François Lagrost

Shakuhachi notation

Some weird facts for a Western musician

- When beginning the shakuhachi, traditional notation is a surprise

- Then, you discover that there are several traditional notations

- And then, that the notation for koto and shamisen is yet something else

- Maybe you can do without a conductor for ensemble music...

- ... until you discover that you do not even have the same bars!

My goals today

- Show you that handling several notations is not so complex

- Invite you to cross school boundaries:

reading a new notation may not be the difficult part, but it can stop you - Consider Western notation

A brief history of shakuhachi notations

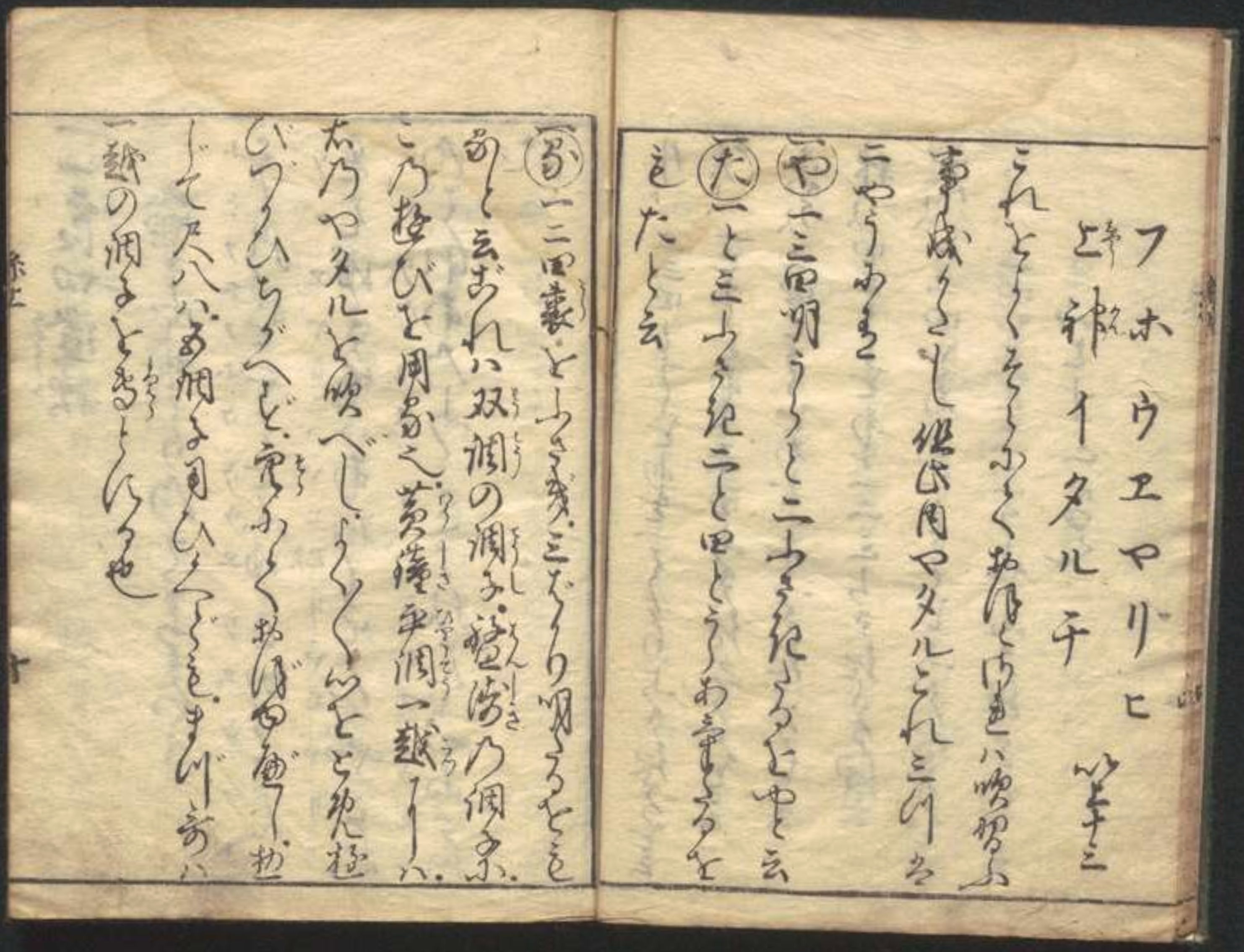

Shakuhachi notation has roots in hitoyogiri notation

Shakuhachi is present in Japan during the Nara period (710-794 CE)

First documented notation system in 1608 in the Tanteki Hiden Fu

(Secret pieces for the short flute)

1664: Shichiku Shoshinshu (Self-help guidebook on musical instruments)

Fu Ho U notations

Hitoyogiri notation with 13 syllables (katakana) representing different notes:

fu フ i イ ya ヤ chi チ ho ホ u ウ e エ

ri リ hi ヒ kan 神 ta タ ru ル shō 上.

Some shakuhachi players changed the hitoyogiri notation and used:

fu フ ho ホ u ウ we ヱ ya ヤ i イ

for the basic fingerings of the shakuhachi

Fu Ho U notations are used in some schools:

- The Kyū Myōan schools such as Kichiku Ryū and Shimpō Ryū

- Chikuho Ryū, although its notation is quite different

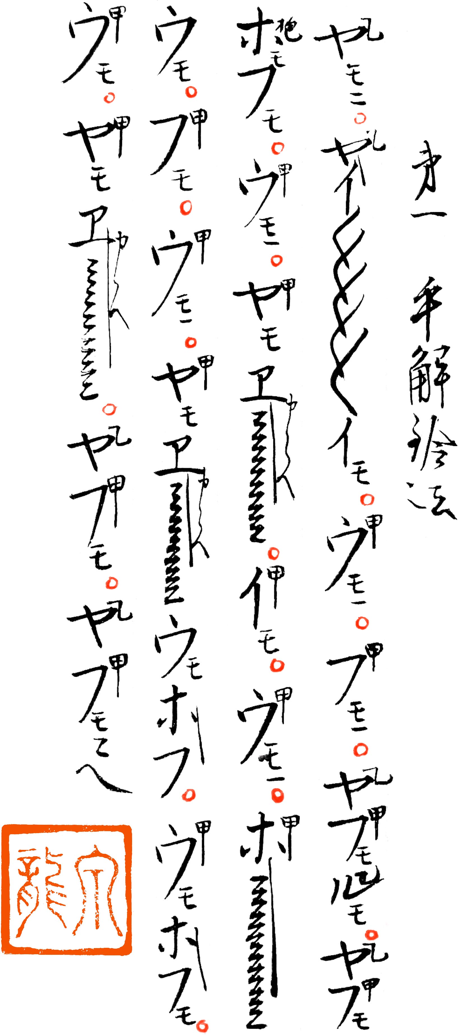

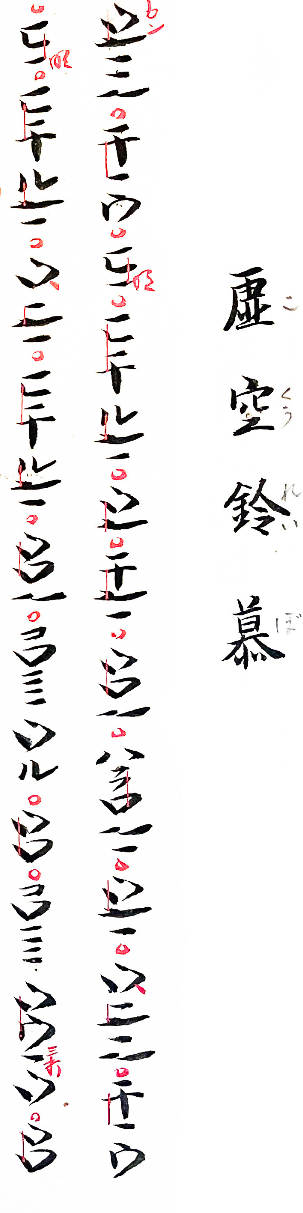

Kyū Myōan notation

Kyū Myōan fingering chartsource: Justin Senryū

Tehodoki Reiho, Kichiku Ryū - Justin Senryū

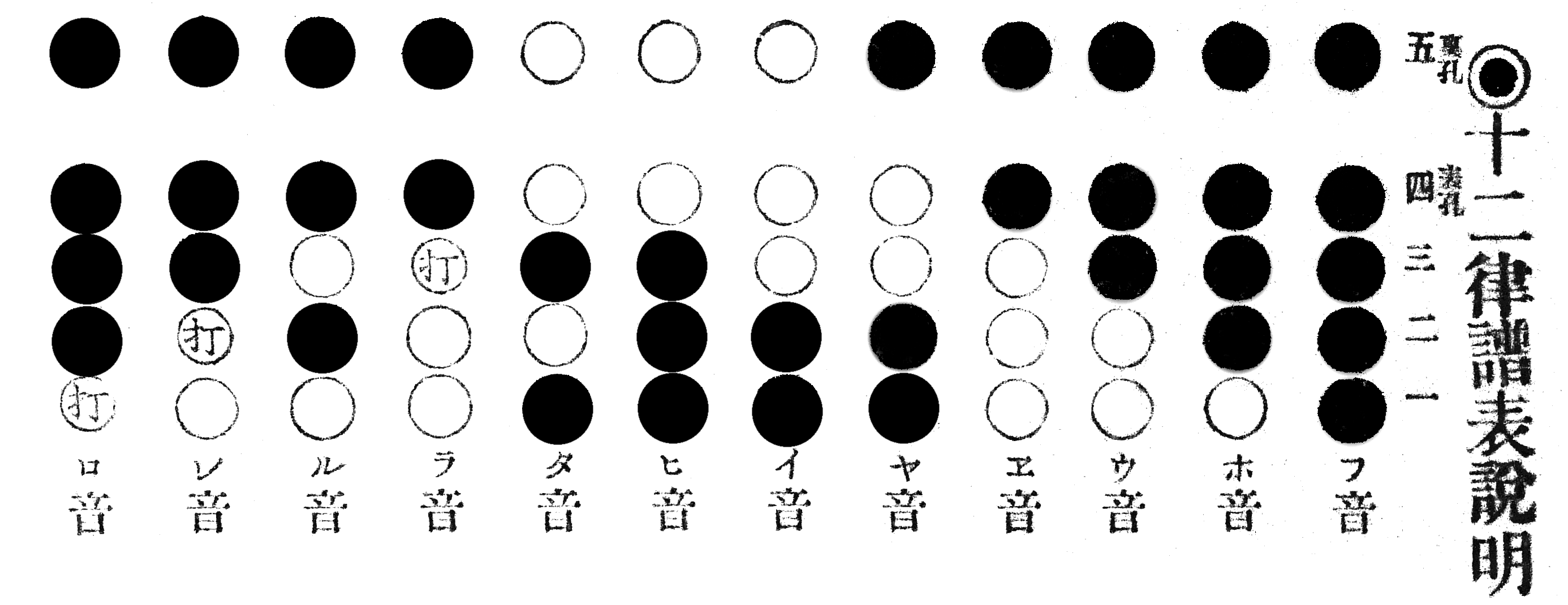

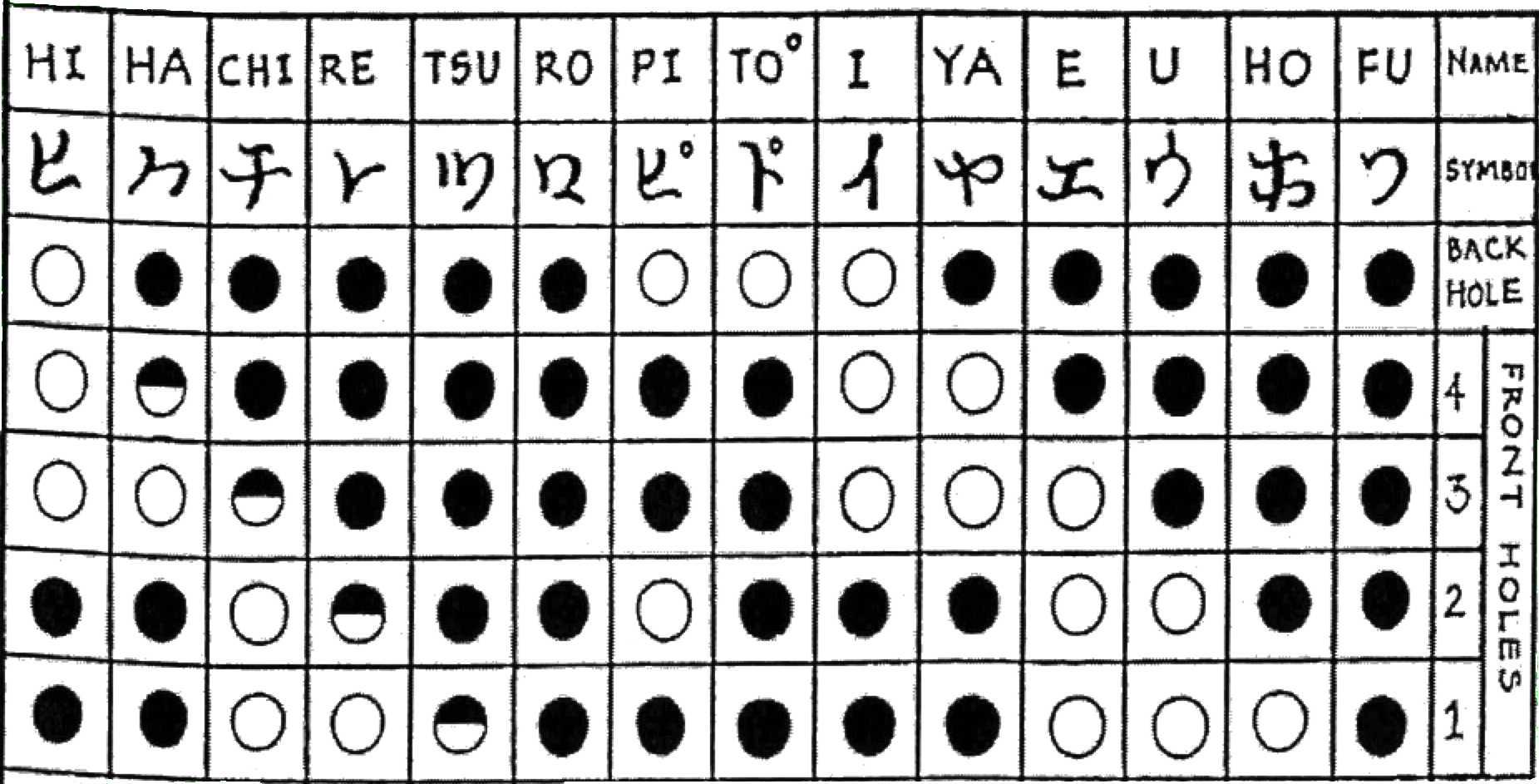

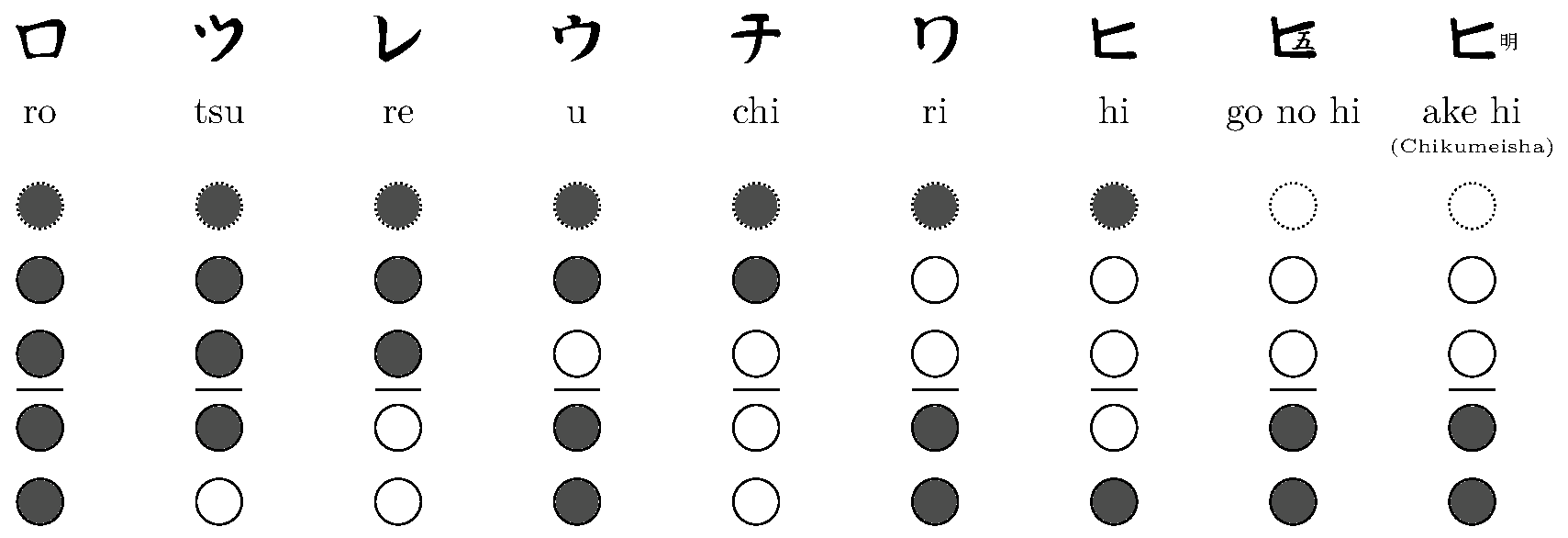

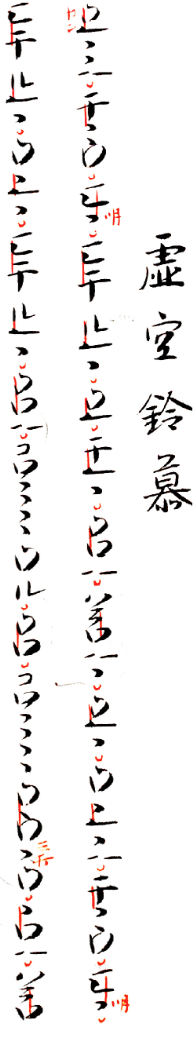

Chikuho Ryū notation

Chikuho Ryū fingering chartsource: Jean-François Lagrost

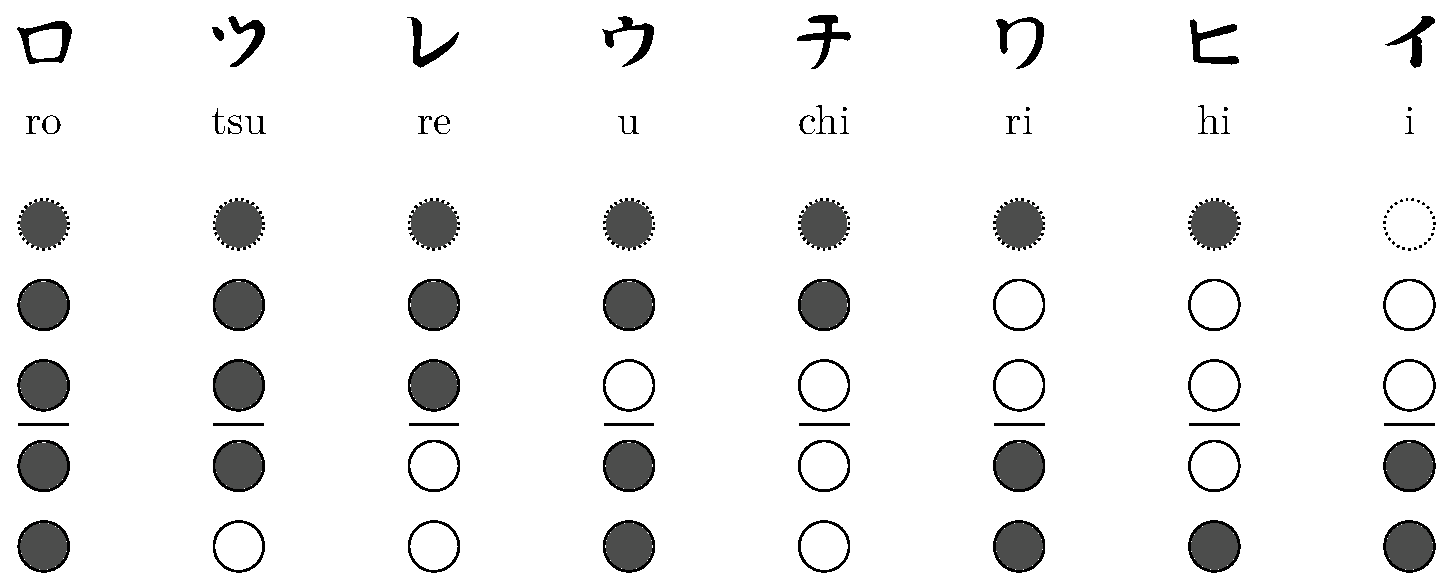

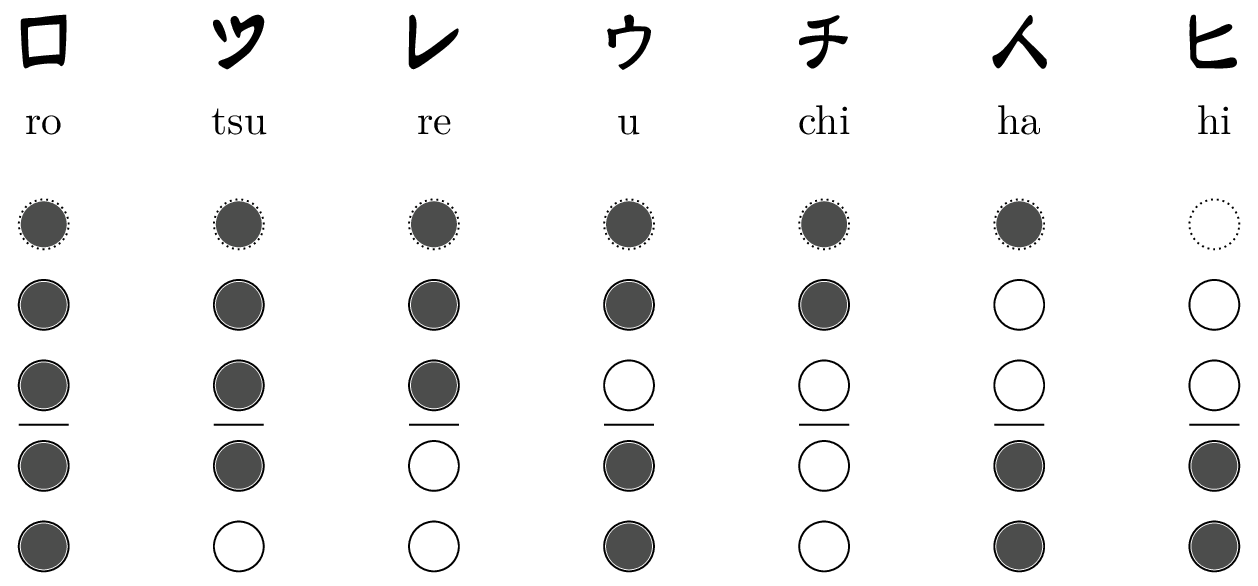

Ro Tsu Re notations

some players developed a notation that uses the letters

ro ロ tsu ツ re レ

instead offu フ ho ホ u ウ

These Ro Tsu Re notations are now the most prevalent:

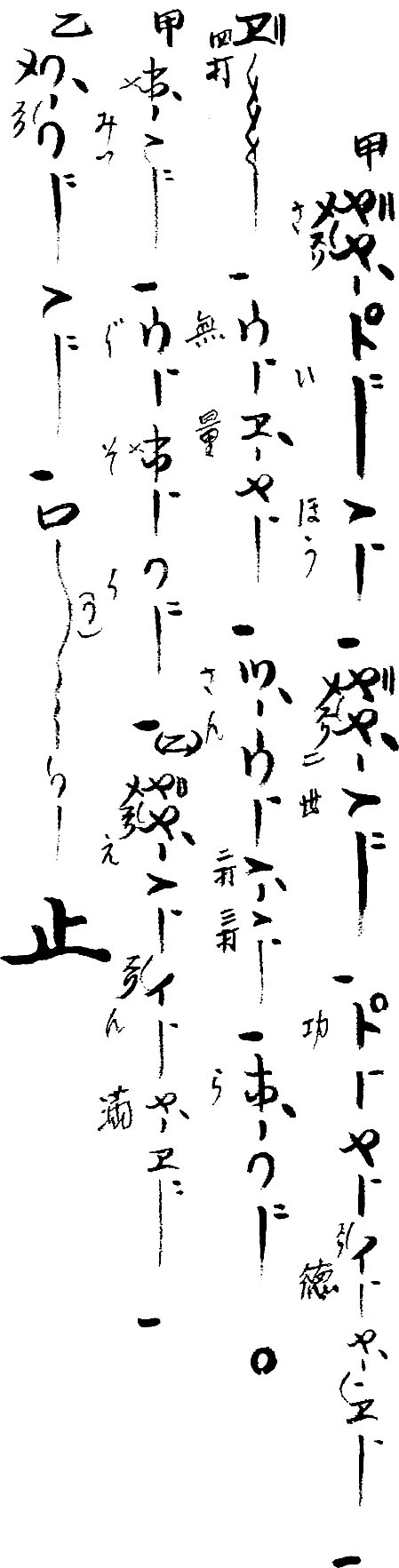

- The Kinko notation, initiated by Araki Kodo II

and developed during the XIXth century by Araki Kodo III

+ rythm notation by Uehara Rokushiro and Kawase Junsuke - The Tozan notation, developed by Nakao Tozan

after the Meiji restauration - There are variations around these two main notations

that we may consider as families of notations.

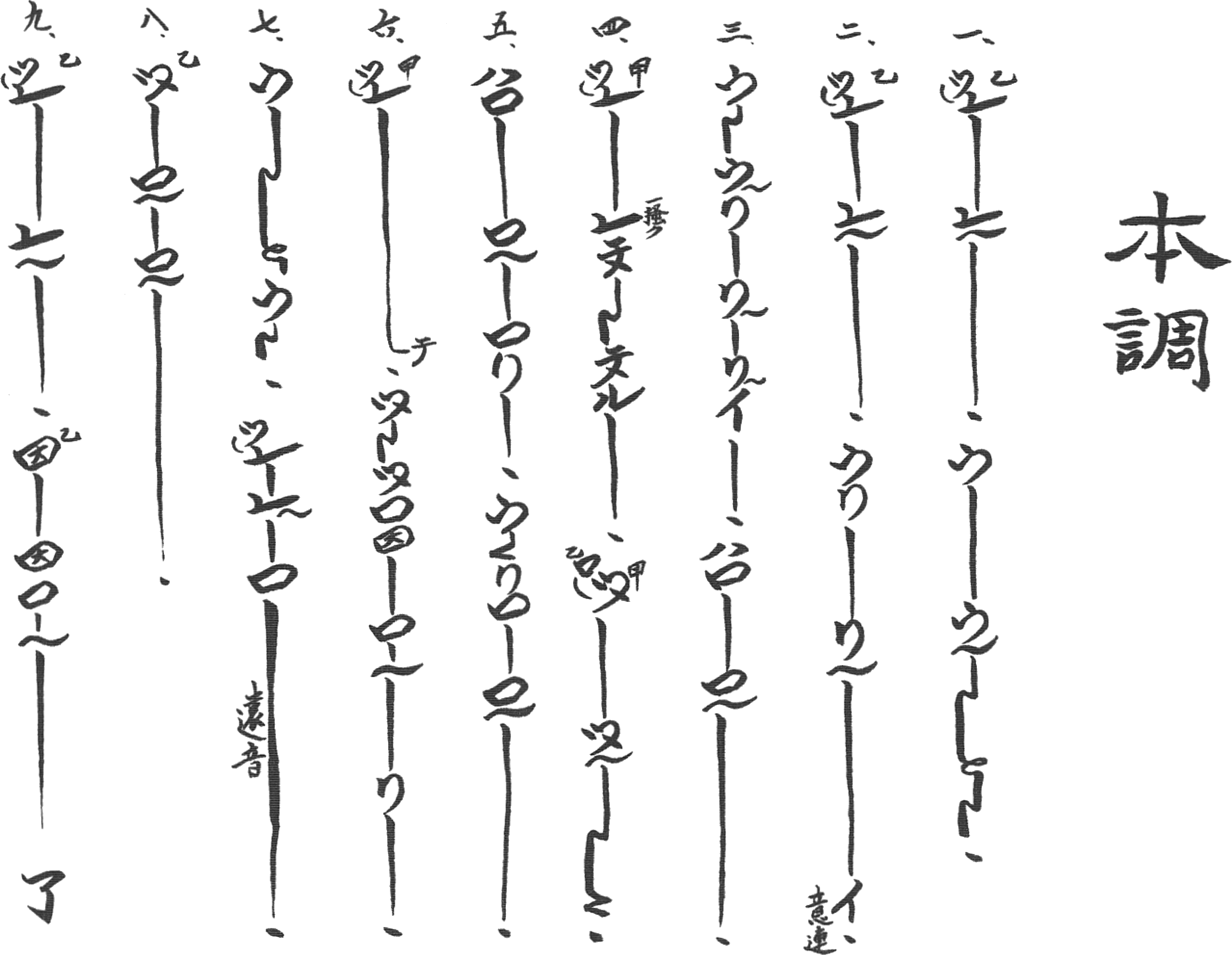

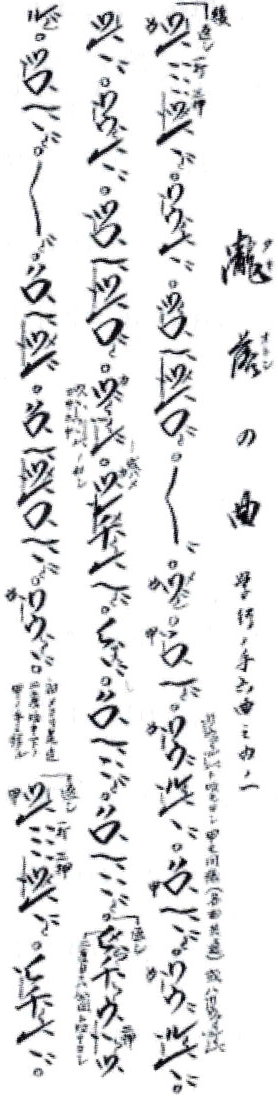

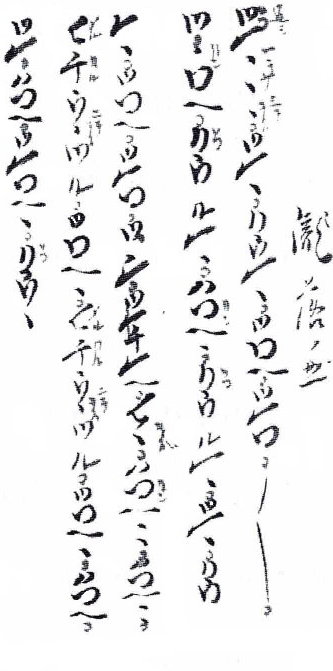

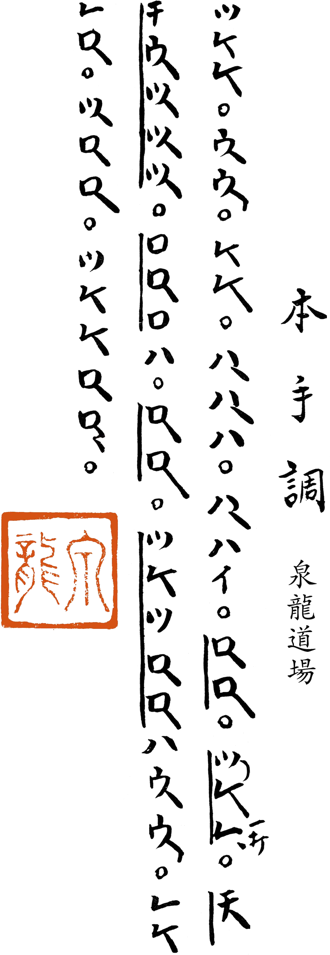

KSK / Chikushin Kai honkyoku notation

Notation ➛ fingering

- Duration?

- Pitch?

- Octave?

- Sequences (katas)?

Duration of notes

In the KSK honkyoku notation:

Lines indicate duration by their length

There is no tempo, the sound is stretched through time according to:

- the style of the school

- the mindset of the player

- the stamina and condition of the player

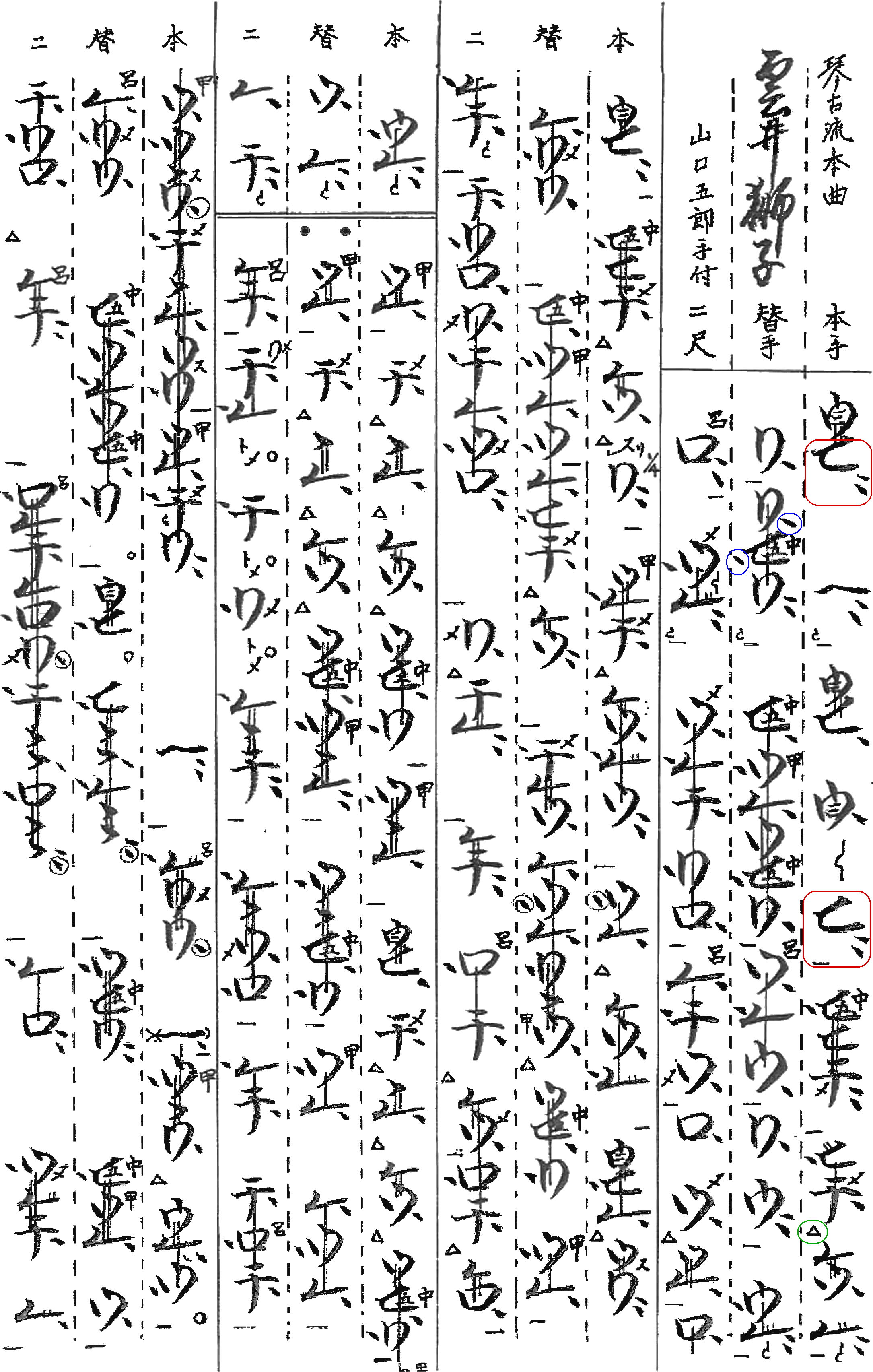

Sankyoku and renkan notation

Synchronization of the players requires a more precise timing

Durations in Kinko “dot” notation

Kumoi Jishi, 3 voice version

Omote marks on the right

Ura marks on the left

Single line: twice as short notes

or grace note

Triangles indicate beats where no note starts

Notes fill in the space between marks:

the first and the third ヒ do not have the same

duration although they have two omote marks!

Durations in Kinko “dot” notation

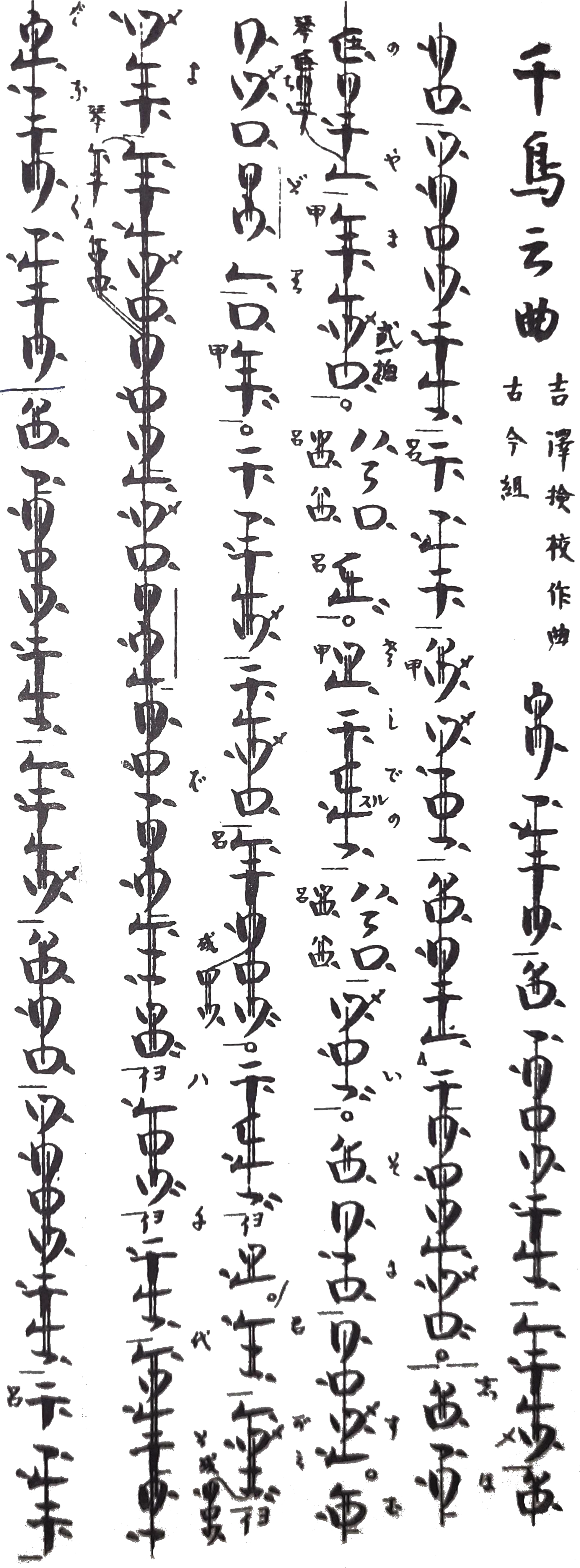

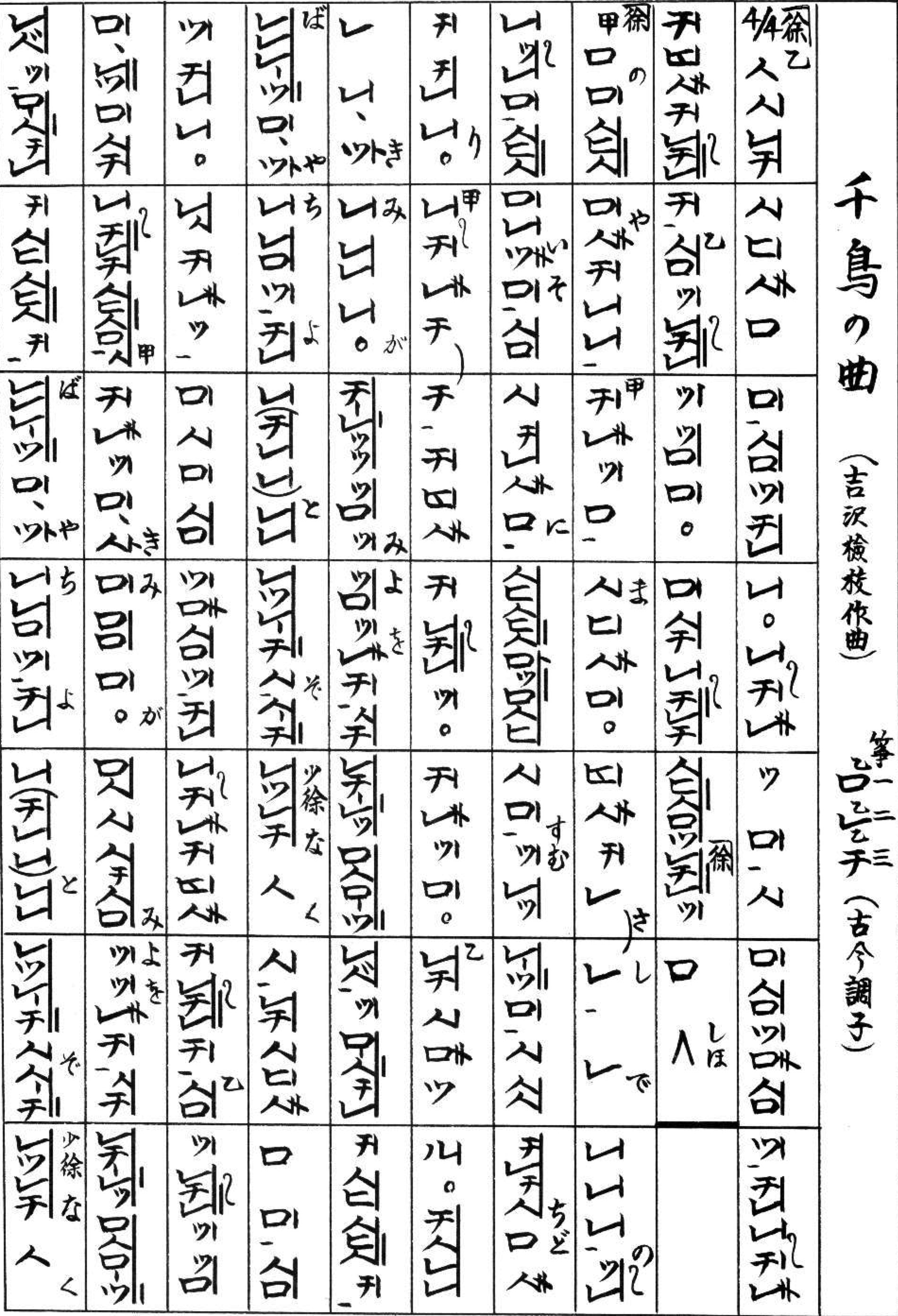

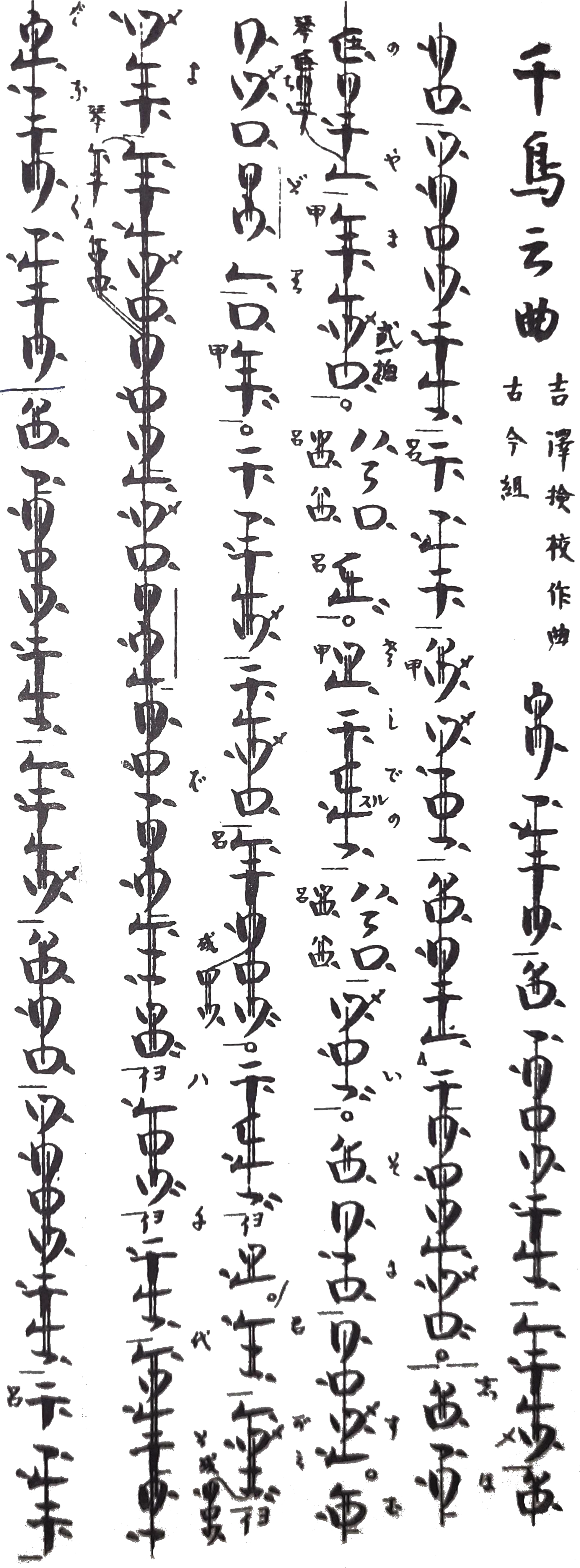

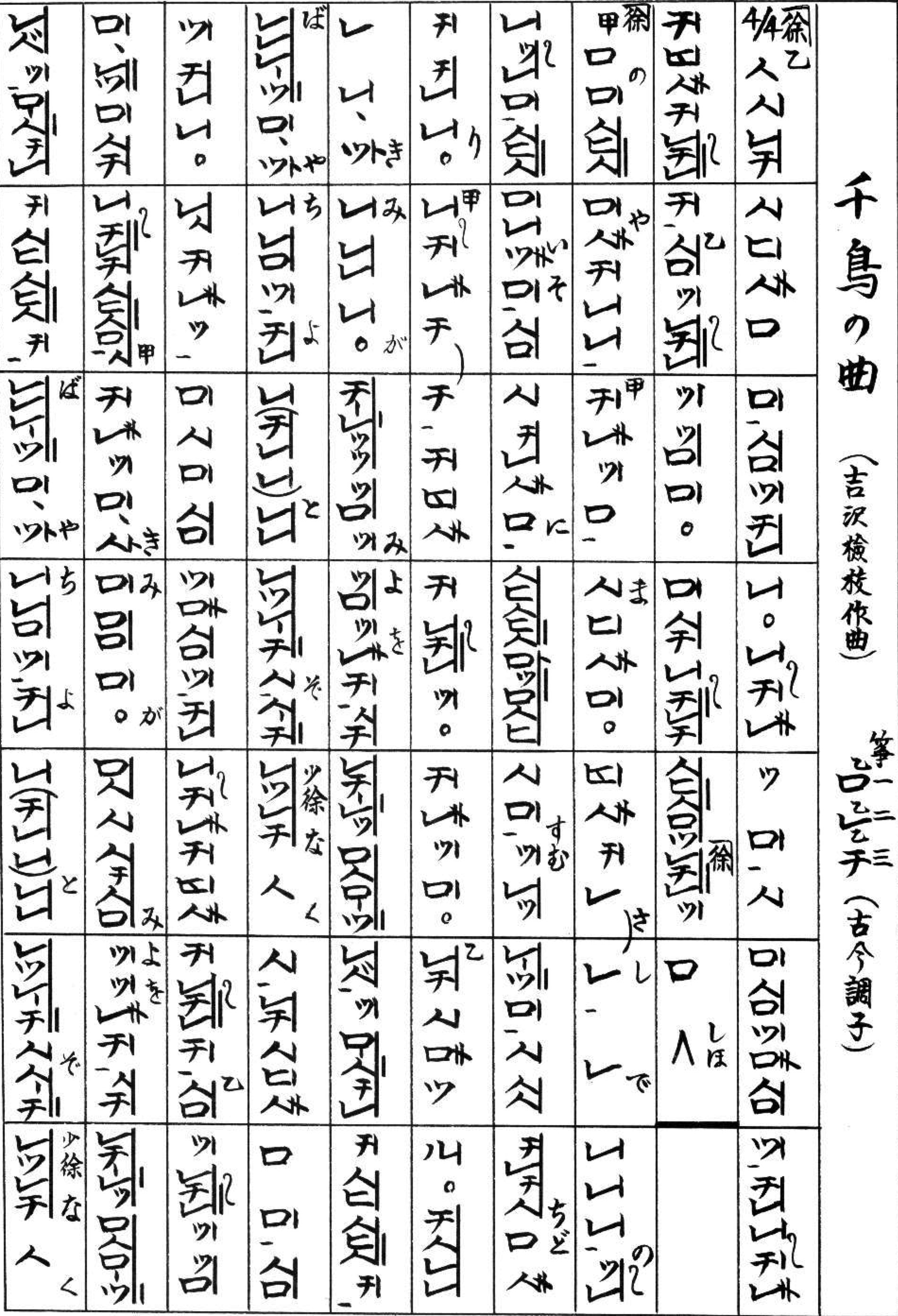

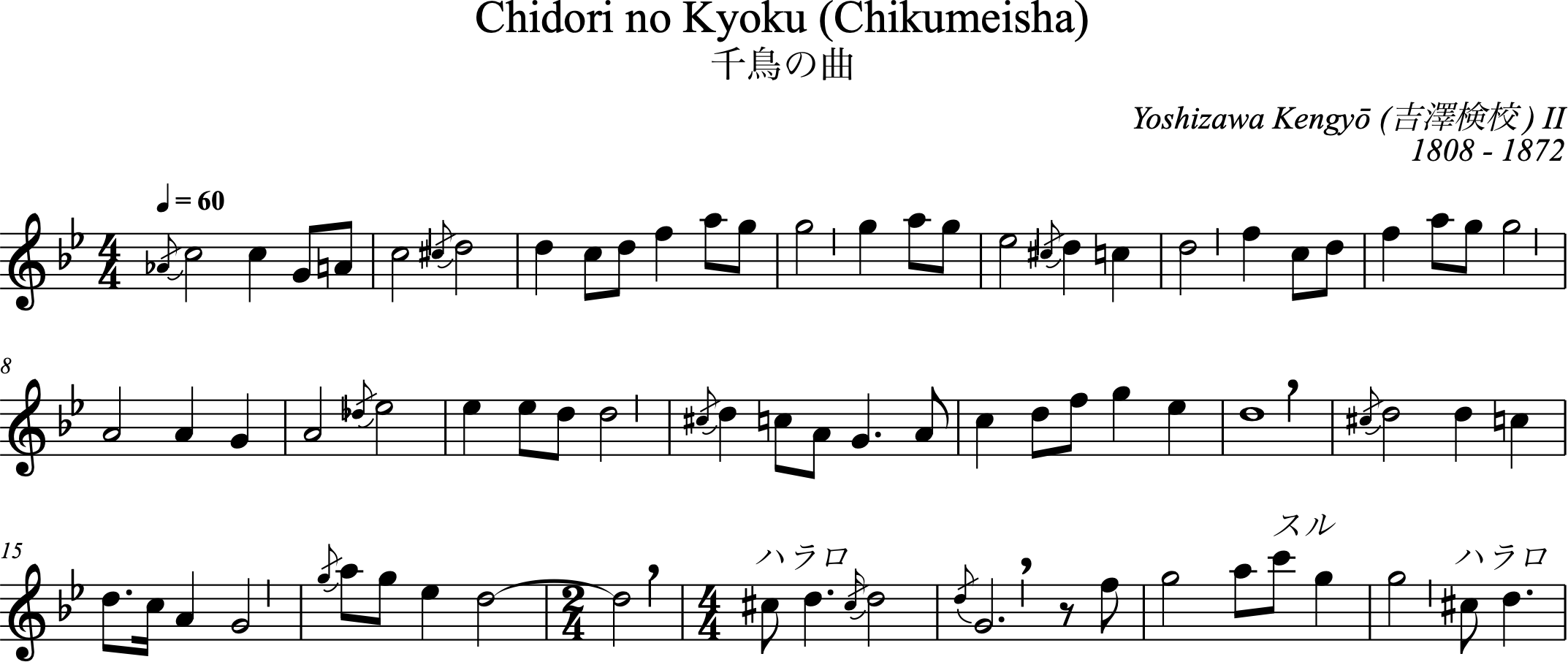

Another example: Chidori no Kyoku

This notation of Chidori no Kyoku was written by Miura Kindō, who studied with Araki Kodo II

and Uehara Rokushirō, and published by the Chikuyūsha guild of Kinko-ryū.

It differs slightly from the notation of Araki Kodo II, III and IV.

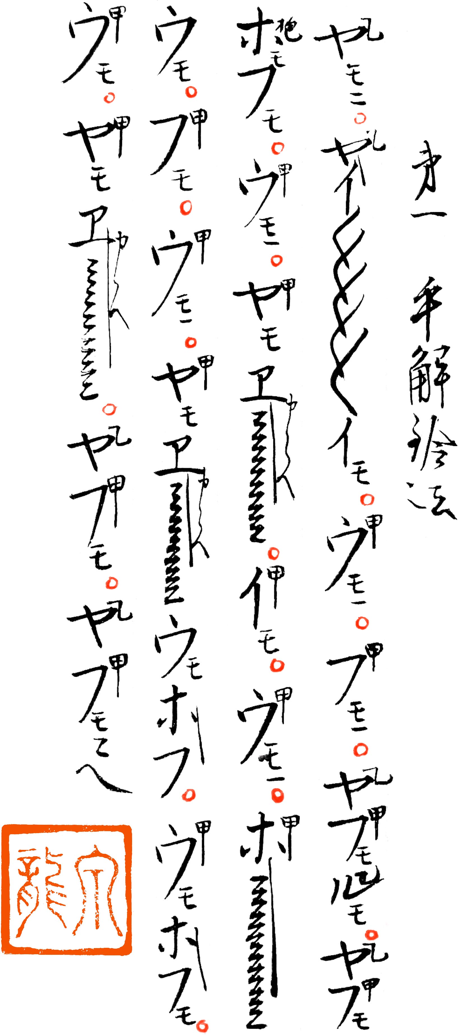

Durations in other notations

タコ足 Tako ashi

(octopus legs)

Seien Ryū

モ style

Kyū Myōan notation

モ makes the duration longer

Each mark under モ makes it even longer

A vertical line beside notes makes them shorter

Tozan notation

Compared to Kinko notation

- Uses ɴ (ha) instead of Ĥ (ri) and ɶ (hi)

- Uses ɶ (hi) instead of ĩ (go no hi)

Durations

- Influenced by western notation

- Time signature and bars

- Notes have a proper duration

- Rests are explicitly notated

- Side lines indicate duration

Pitch

Shakuhachi notations indicate fingering

Variations in pitch can be shown by vertical lines

or by indications such as 引き (hiki: pull)

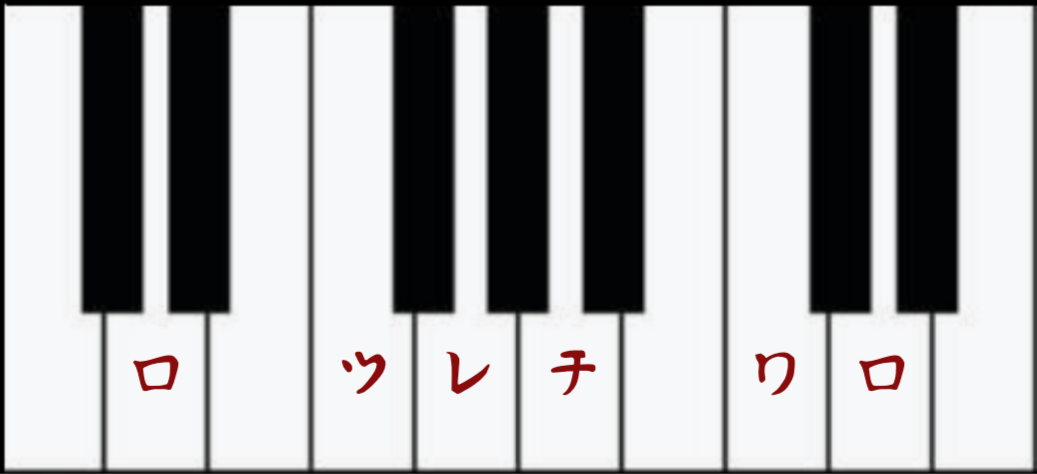

Pitch of the “natural” notes of a 1.8 shakuhachi shown on a piano keyboard:

There are missing pitches...

Pitch

Meri / Kari notes

The pitch of the basic notes is changed by the meri or kari

position of the embouchure, and by partially closing holes

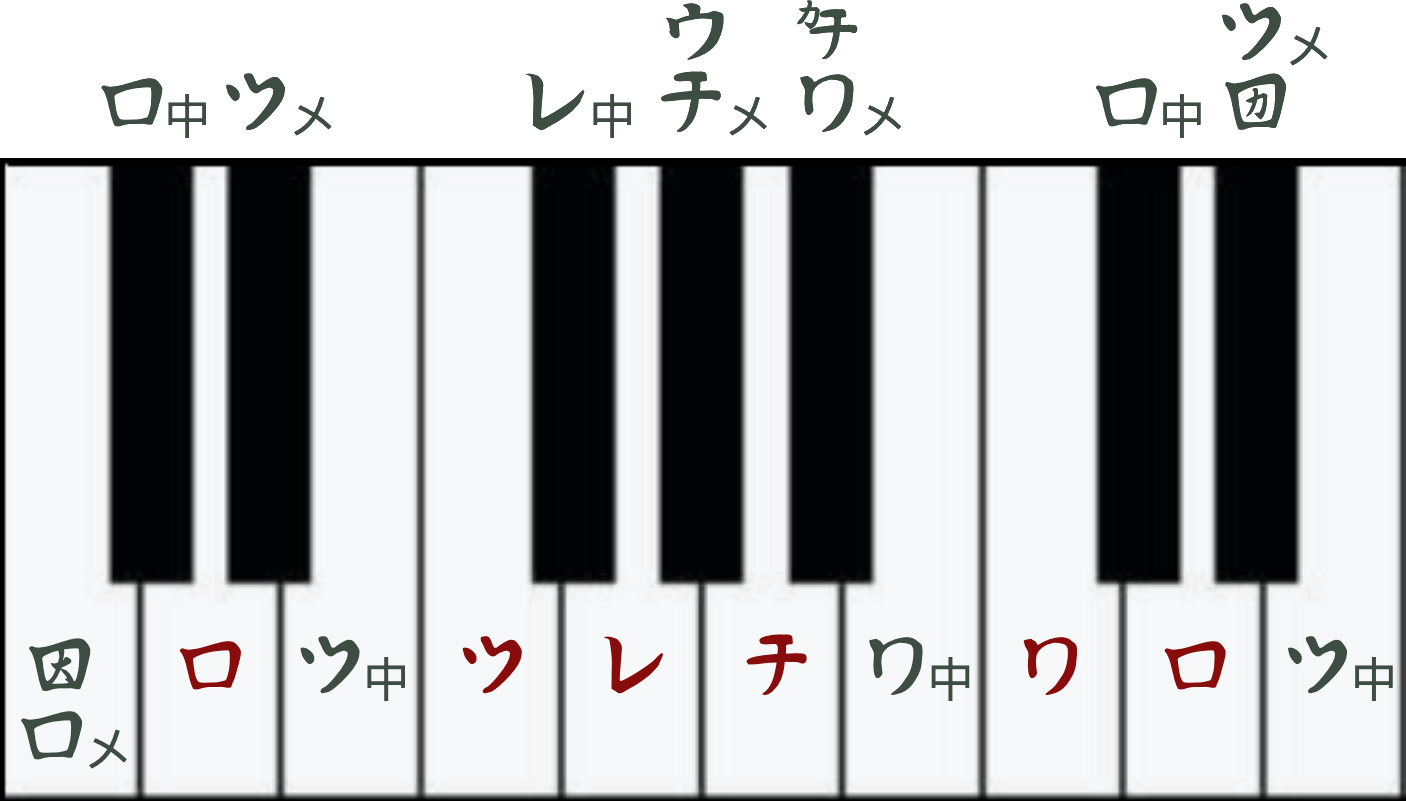

In Kinko notations

There are three kinds of meri: small, normal, and deep

Basically:

- chū meri (中メ) lowers the note by a half step

- meri (メ) lowers the note by a full or a half step

- dai meri (大メ) lowers the note by a full step

Examples:

- chū meri tsu ě中 is a half step below tsu ě

- tsu meri ěメ is a full step below tsu ě

However:

- chi meri Ģメ is a half step below chi Ģ

- but re meri Ğメ is generally the pitch of tsu.

- ro meri Ęメ may be a half step below ro,

with ro dai meri (or ō-meri) Ė a full step below ro

In Tozan notation

- a small note is a half step above the note below

small tsu ɨ is a half step above ro ɧ - meri (メ) lowers the note by a half step

tsu meri ɩ is a half step below tsu ɪ - small re ɬ is a half step above tsu ɪ

small re meri ʈ is the pitch of tsu ɪ

Pitch

Meri and kari notes shown on a piano keyboard

Comparing pitch variation notations

KSK / Chikushin Kai

(turned 90°)

Neumes

(Gregorian chant

in Western Europe)

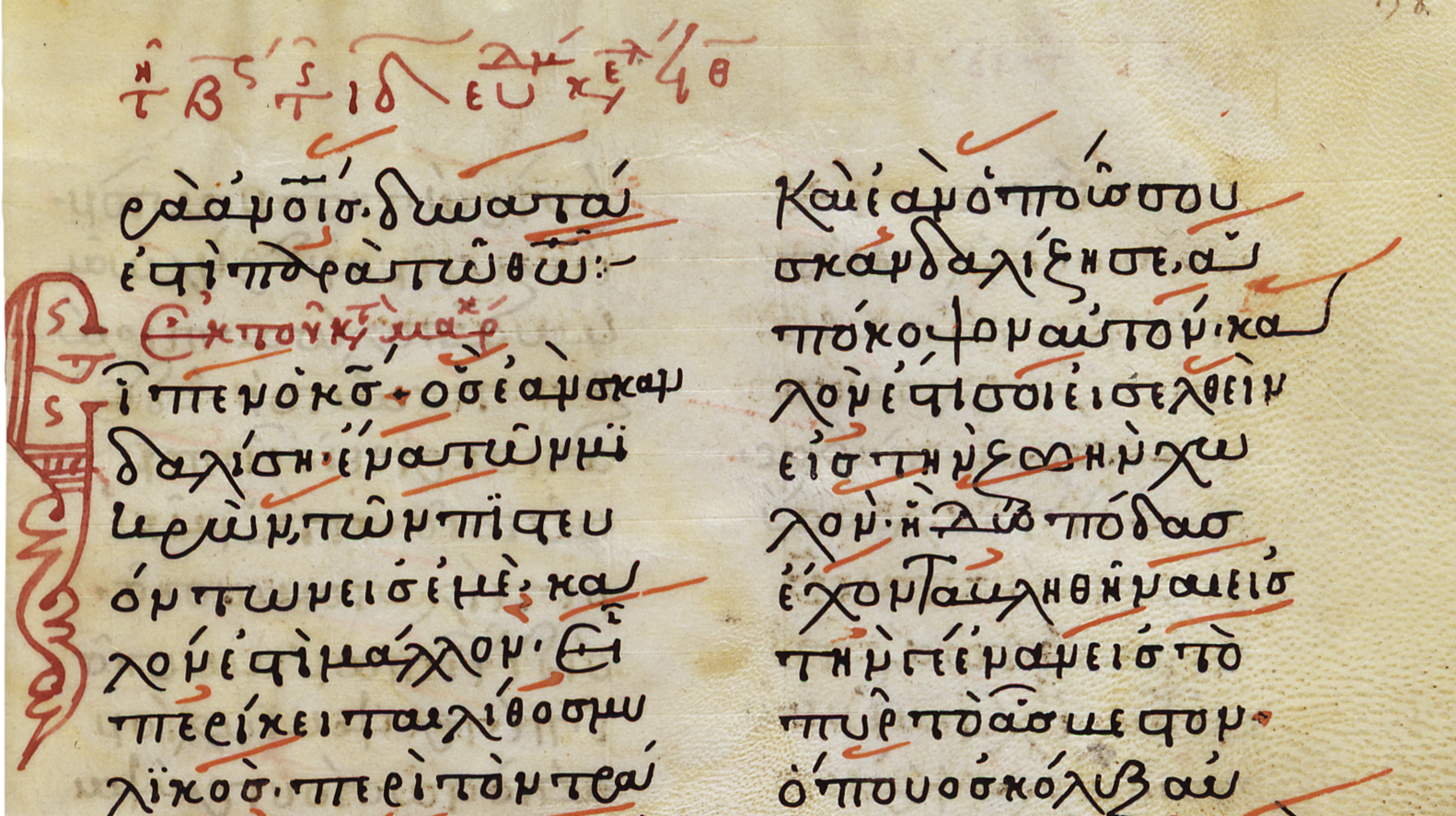

Ekphonetic notation

(Gregorian chant

in Byzantium)

Octaves

- Otsu 乙 / Ryo 呂

Indicates the lower octave. Can also be indicated temporarily by a tenten: đ - Kan 甲

Indicates the second octave, you reach it by blowing with more air speed - Daikan 大甲

In this third octave, the fingerings change

Octave change rules

When you start and end in the range ri Ĥ/ha ɴ to tsu ě,

you change octave, else you stay in the same octave.

For instance

- ïĤě goes to îě

- ïĢě goes to ïě

- îĘɴ goes to ïɴ

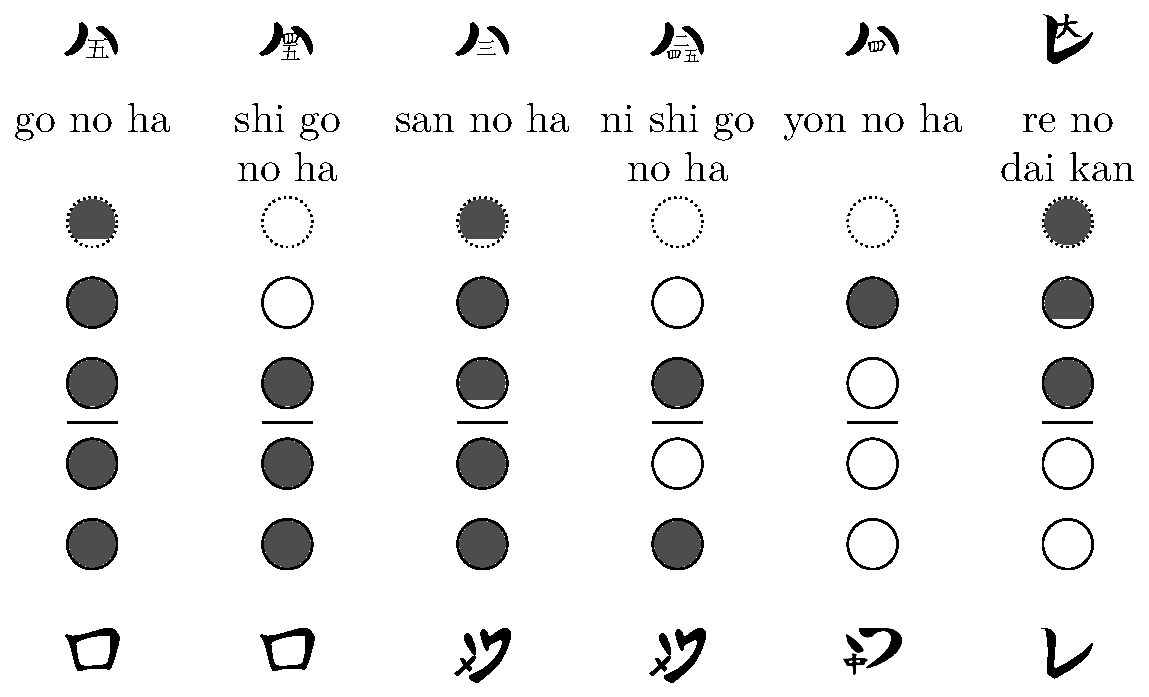

Notations for the third octave

Kinko: a variety of ha

Notations for the third octave

Tozan: from pi up to the sky...

Western notation

Evolved in various monasteries for the notation of Gregorian chant

Converged towards the modern Western notation through exchanges

Western notation

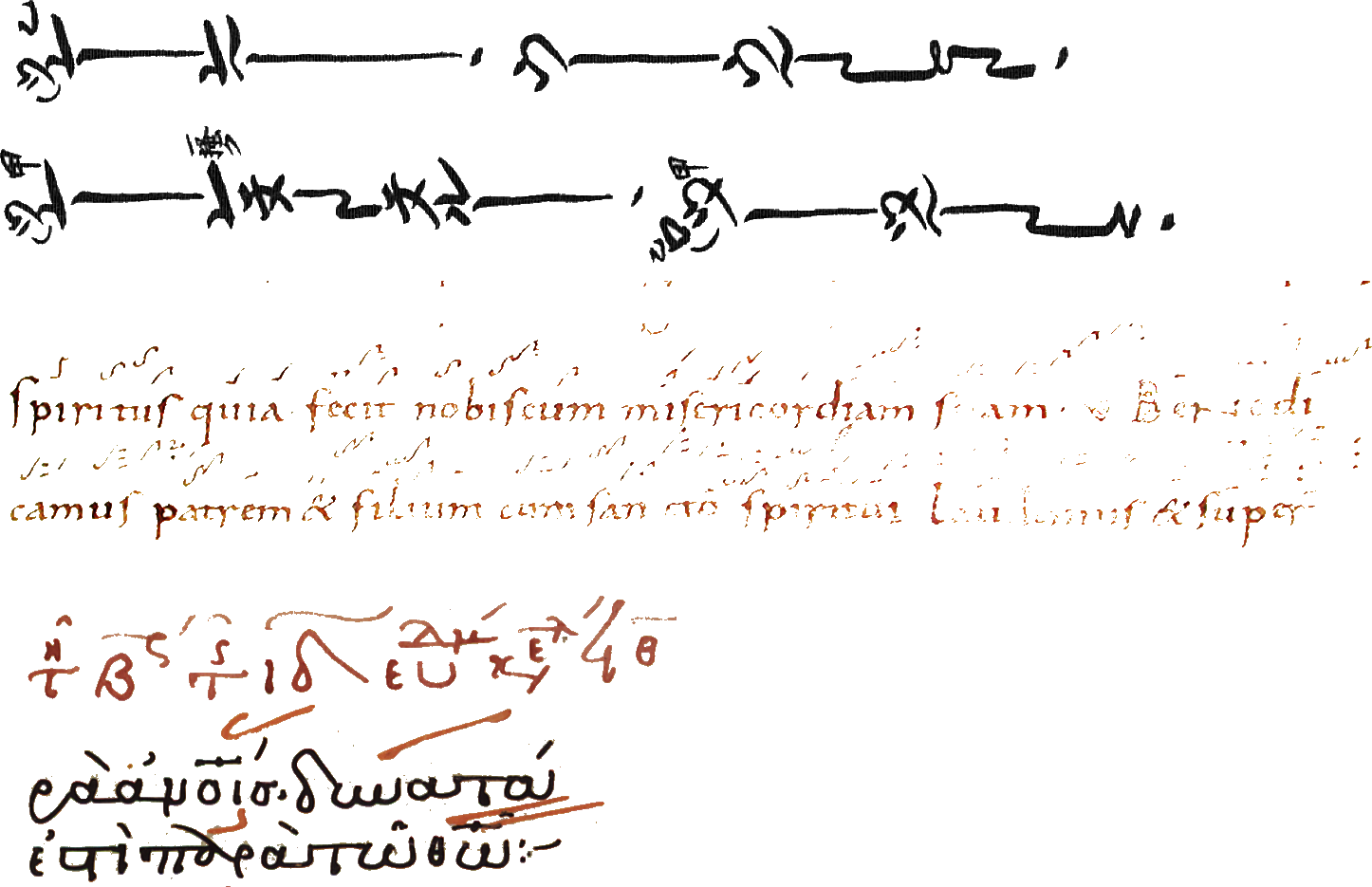

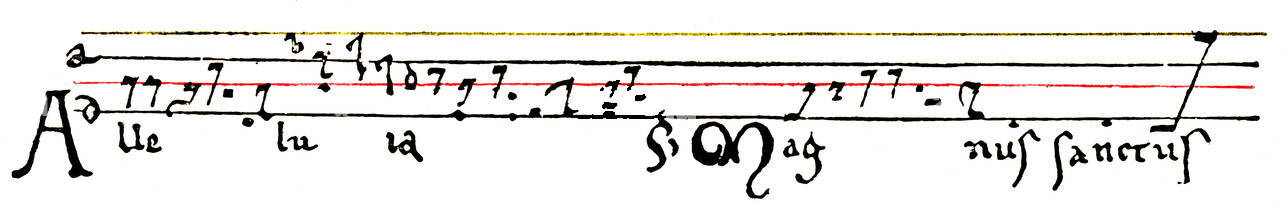

Neumes for Gregorian chant (Saint Gall neumes, Xth century)

Source: French National Library

Western notation

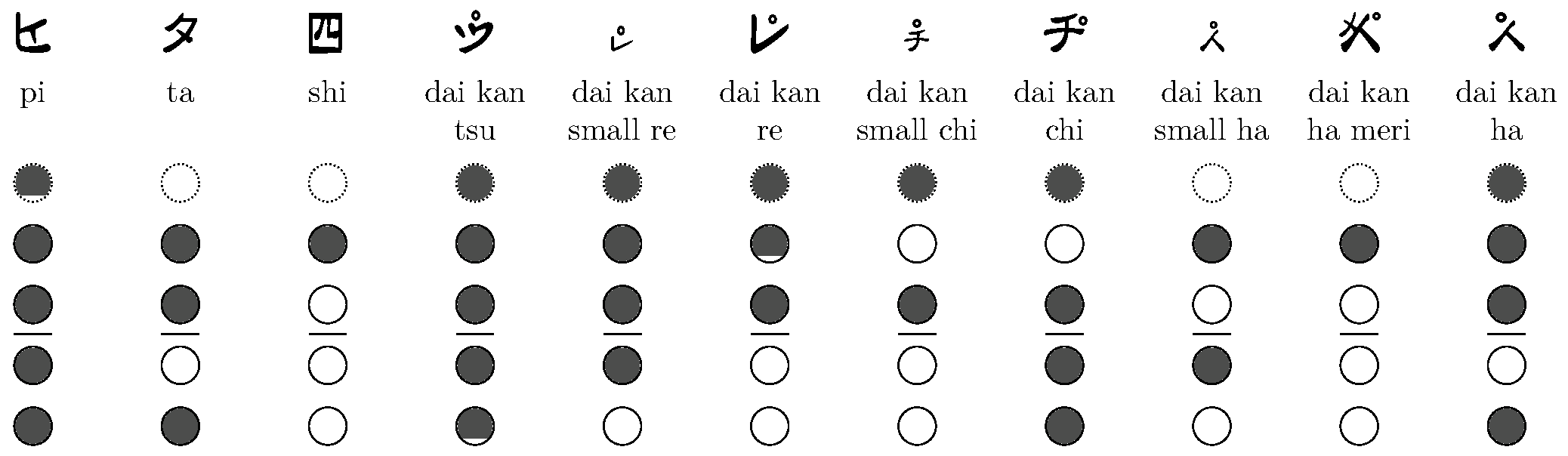

Ekphonetic notation (Bizantium, IXth to XIVth century)

Source: French National Library

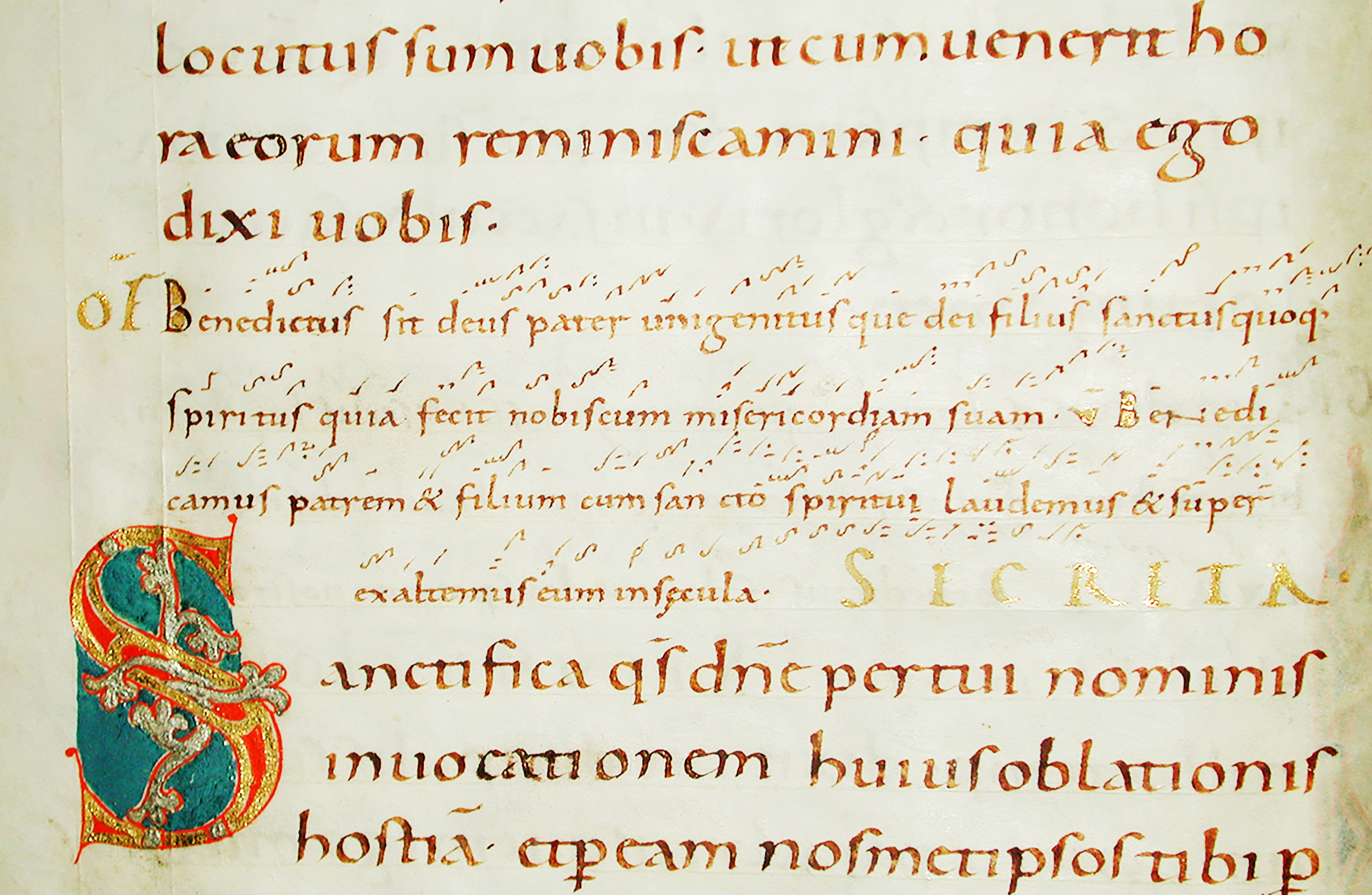

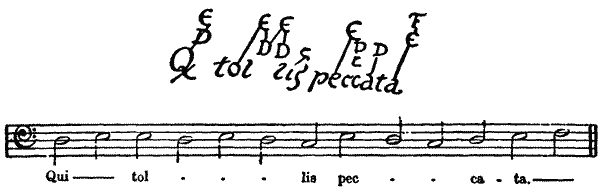

Western notation

Notations of Guido d'Arezzo (992 - 1033)

Letter notation, with its translation below

Neume notation. The red line indicates F, the green/yellow line indicates C

Source: Project Gutenberg, A Popular History of the Art of Music, by W. S. B. Mathews

Western notation

Codex Las Huelgas (~1330)

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Western notation

Collection of Italian cantata (XVIIth century)

Source: French National Library

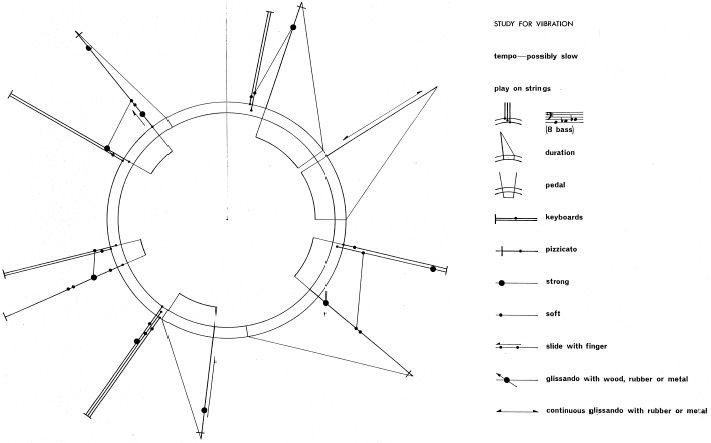

Graphical forms of notation

Toru Takemitsu

Study for Vibration

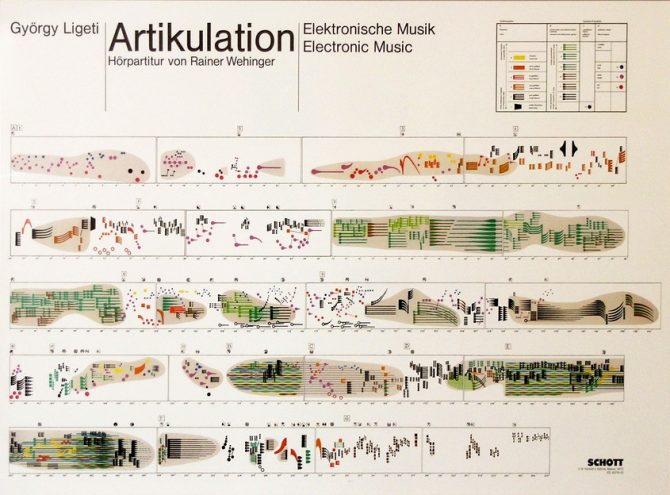

Graphical forms of notation

György Ligeti

Artikulation

Western notation

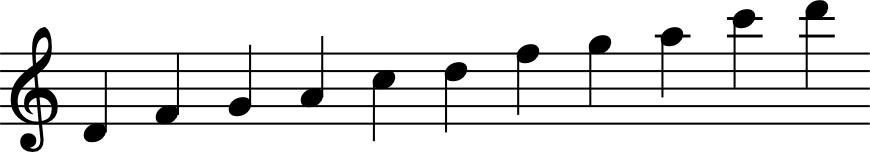

Western notation uses dots placed on a five line staff

The pitch of the notes is given by a key, we consider only the treble key here

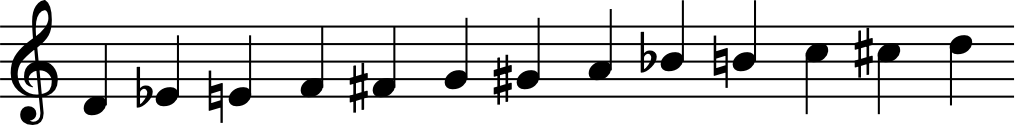

Natural notes of a 1.8 shakuhachi:

Variations in pitch are indicated by sharps (♯), flats (♭), and naturals (♮)

Durations are indicated by the shape of the note.

Bars group units of time indicated by a time signature

Default pitch alterations are indicated by a key signature

Transposing instruments

Western notation does not always indicate pitch

Some families of instruments exist in different sizes,

so a given fingering does not yield the same pitch on all instruments

Examples

Clarinets

- The fingering of C on a “regular” clarinet yields a B flat

- The fingering of C on an A clarinet yields an A

- The fingering of C on a basset horn yields an F

- The fingering of C on a bass clarinet yields a B flat one octave lower

Saxophones

- The soprano saxophone is in B flat (the fingering of C yields a B flat)

- The “regular” alto saxophone is in E flat (the fingering of C yields an E flat)

- The tenor saxophone is in B flat

- The barytone saxophone is in E flat

Western notation for shakuhachi

In Western music vocabulary, an instrument is in X if

the fingering for C on this instrument produces the pitch of X

What is the fingering of C on a shakuhachi?

“Normal” 1.8 shakuhachi: the pitch of C is obtained with ɱ (ri)/ɴ (ha)

⇒ ɱ/ɴ is considered as the fingering of C on the shakuhachi

Therefore:

- the 1.8 shakuhachi is in C (by definition)

- the 1.6 shakuhachi is in D

- the 2.0 shakuhachi is in B flat

- the 2.4 shakuhachi is in G

Lowest note (ro)

- D on a 1.8 shakuhachi

- E on a 1.6 shakuhachi

- C on a 2.0 shakuhachi

- A on a 2.4 shakuhachi

When specifying shakuhachi pitch, it seems safer to give

both the expected pitch of ro and the length of the shakuhachi

Prefer “a 2.0 shakuhachi, ro = C” to “a B flat shakuhachi”, or “a C shakuhachi”

Chosing the right shakuhachi

for a Western notation

- Ambitus: you should be able to play all written pitches:

- Nothing too low

- Nothing too high

- Ease of play: you may avoid notes that are difficult to play

- Avoid key signatures with sharps

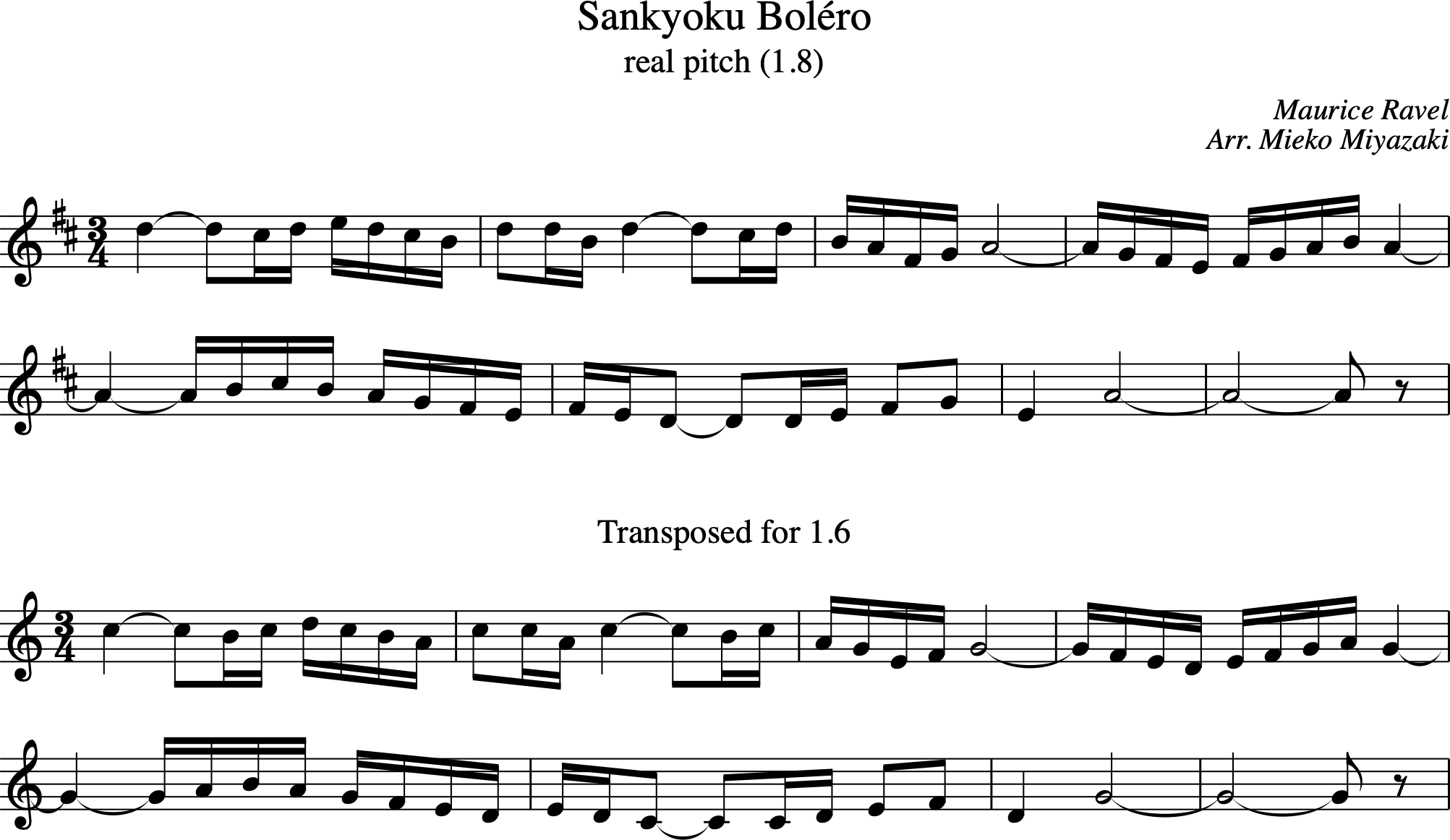

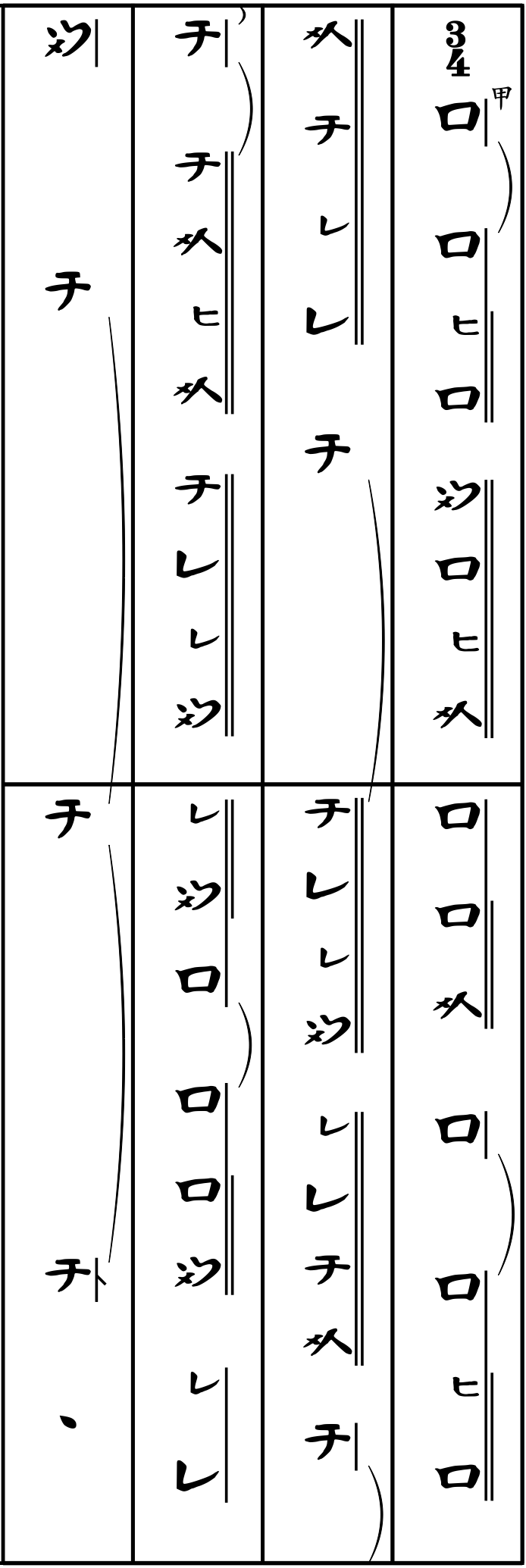

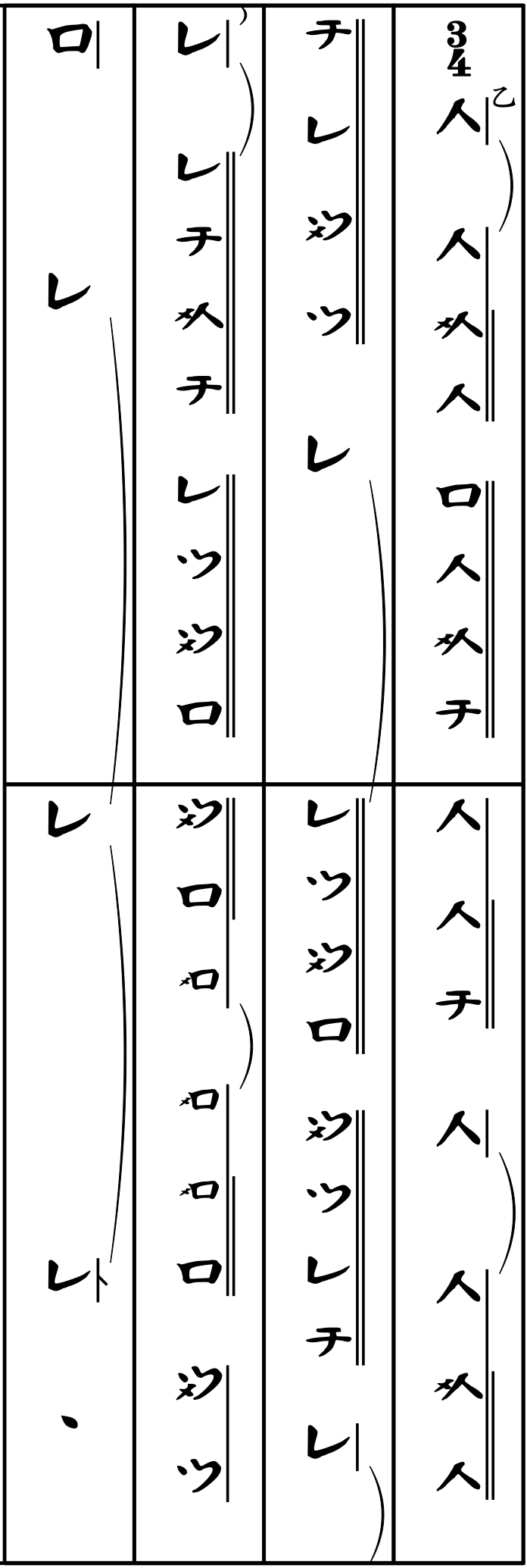

- Example: Ravel's Bolero

- Style: you may want that some pitch falls on a meri note

- Some tunes require a special tone color on some notes

- Example: Sakura (extract from “Japanese Tune”, a piece for wind ensemble)

Example: Ravel's boléro

Clarinet in C

1.8 shakuhachi

1.6 shakuhachi

Example: Ravel's boléro

For 1.6

For 1.6

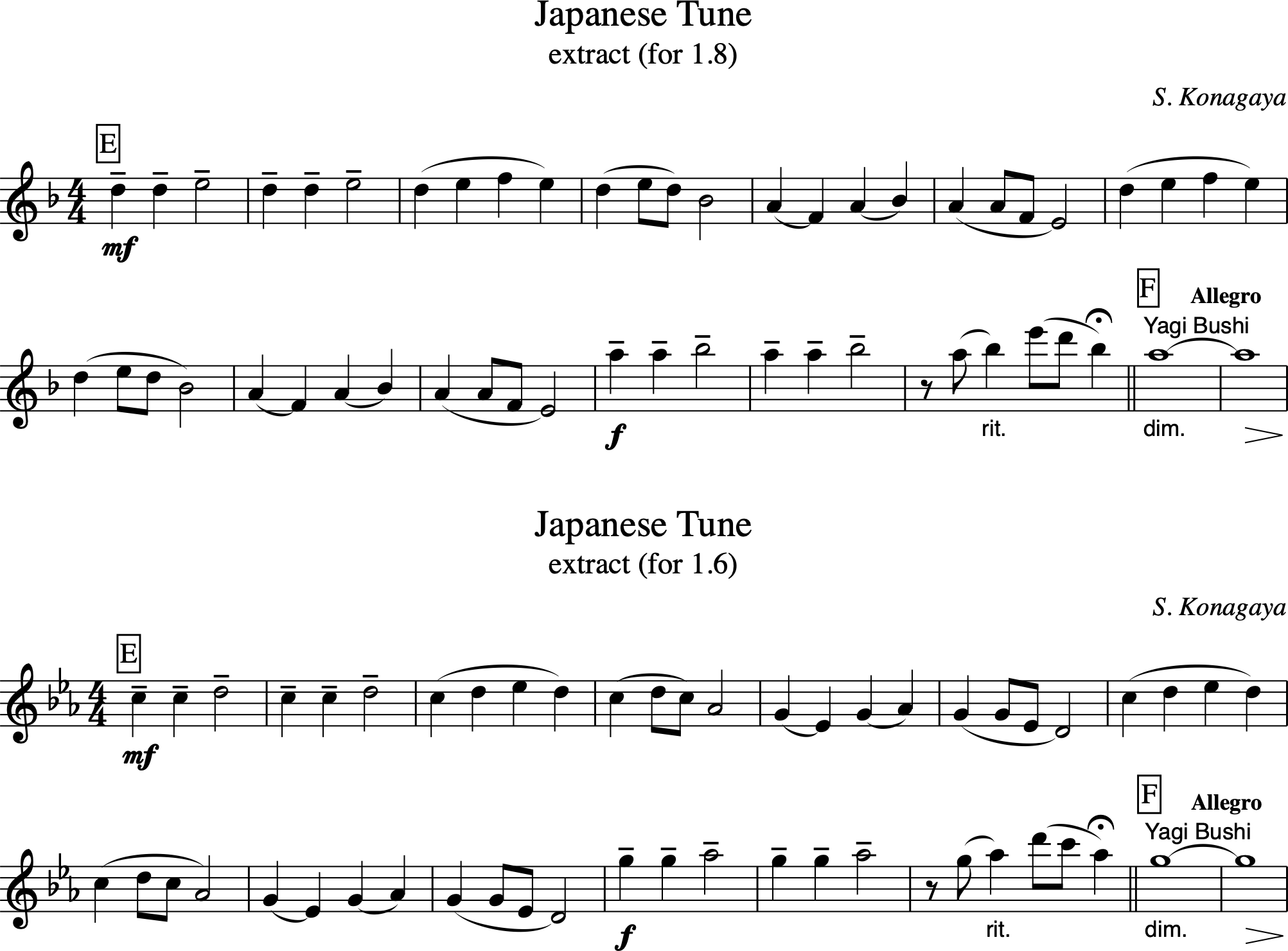

Example: Japanese Tune (Sakura)

1.8 shakuhachi

1.6 shakuhachi

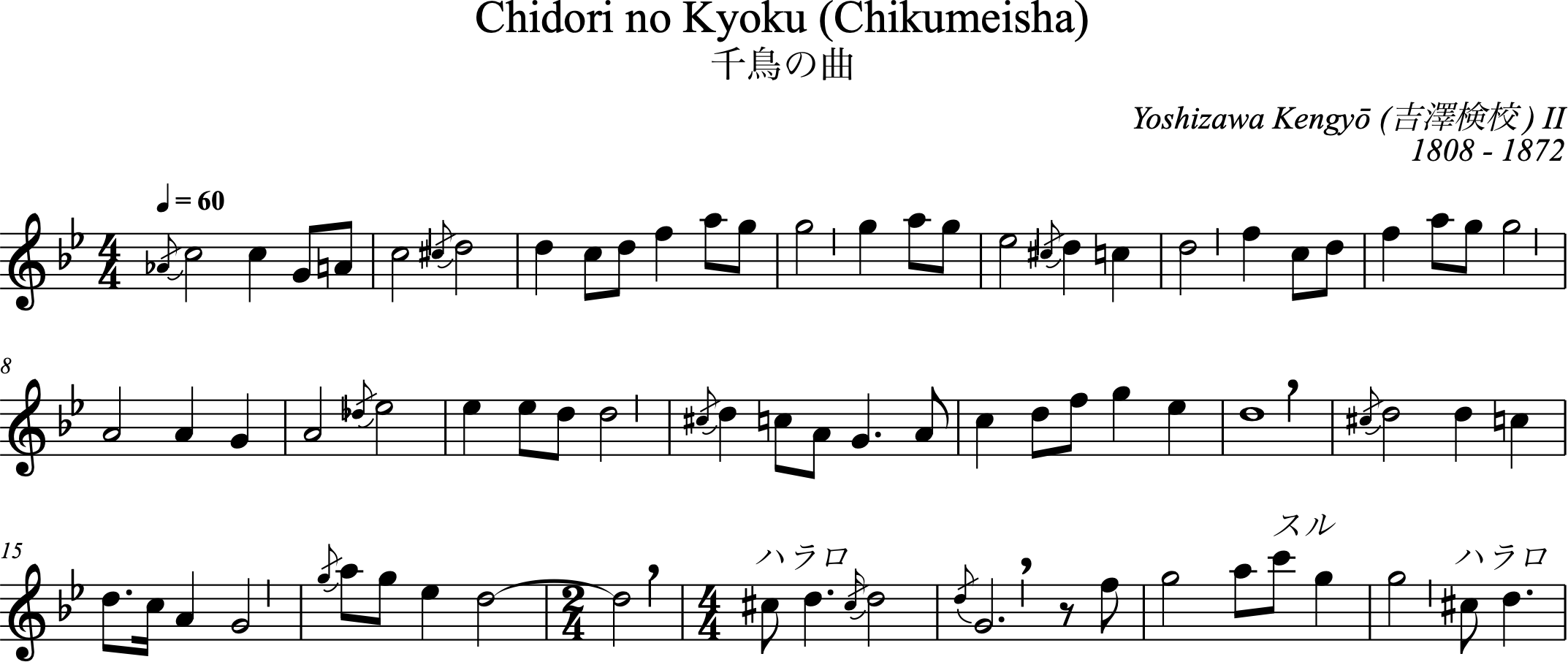

Shakuhachi music in Western notation

Example: Chidori no Kyoku with flute players

- No tonging, finger attacks

- Special articulations, suri age etc.

- Special tone color of some notes

- Beware of transposing instruments (clarinets, saxophones, trumpets)

Several flavours of Chidori no Kyoku

Conclusion

Reading a notation is not playing the style of a school

Reading several notations helps playing in various circumstances

Being able to read Western notation opens opportunities

outside the domain of traditional Japanese music

When playing Western notation:

- Consider the length of your shakuhachi

- Beware of the transposition made by the western instrument

- Take care of the range, ease of play and tone colour

Sources

Documents

- Gunnar Jinmei Linder, 2012

“Deconstructing Tradition in Japanese Music

A study of Shakuhachi, Historical Authenticity and Transmission of Tradition” - Gunnar Jinmei Linder, 2010

Notes on Kinko-ryu shakuhachi honkyoku: performance techniques – analysis, classification, explanation - Riley Kelly Lee, 1988

“Fu Ho U vs. Do Re Mi: The Technology of Notation Systems and

Implications of Change in the Shakuhachi Tradition of Japan” - Donald Paul Berger, 1969

“The Shakuhachi and the Kinko Ryū Notation” - The European Shakuhachi Society https://shakuhachisociety.eu

- The International Shakuhachi Society https://www.komuso.com

- The French National Library https://essentiels.bnf.fr

Notation

- Gunnar Jinmei Linder

- Jean-François Lagrost

- Justin Senryū

- Workshops, master-classes, summer schools...

Errors

- 100% mine